Hello world! 2

February 7, 2014

17 Days In Sochi: The Olympics And Social Justice

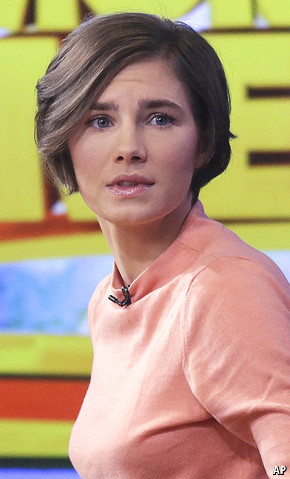

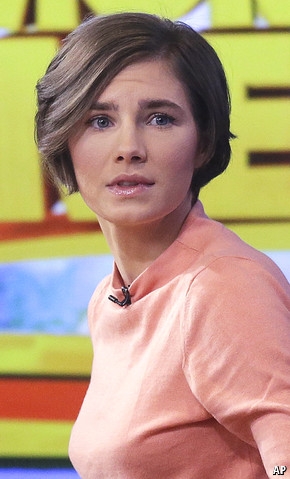

February 7, 2014 Knox’s innocent or guilty face?

Knox’s innocent or guilty face?

NOT for the first time, Americans are seeing Italy with a sort of double vision. In one eye stands a land of exquisite cuisine and glorious heritage (even if it is one that goes unnoticed by uncultured ratings agencies). In the other is a country with a moribund economy, widespread corruption, organised crime, Silvio Berlusconi—and a seemingly absurd and scary court system.

On January 30th appeals-court judges in Florence upheld the conviction of an American student, Amanda Knox, for the murder in 2007 of her British flatmate, Meredith Kercher, and sentenced her to 28½ years in jail. Ms Knox’s Italian former boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, was given 25 years for the same offence. Yet the verdict jarred with some judicial precepts Americans see as fundamental.

No more shirking

First, it appears to violate the principle of double jeopardy (not being prosecuted twice for the same offence), since the couple’s appeal succeeded in another court before the supreme court ordered it to be reheard. Counting pre-trial and trial, this is the fifth time judges have pored over the details of the case. And it is still not over: the defence plans a further appeal, partly because the presiding judge in Florence gave an interview in which he suggested that Mr Sollecito had prejudiced his case by refusing to testify. Americans might here put forward another precept: that justice delayed is justice denied.

The judges’ decision also ignored “reasonable doubt”. None of Ms Knox’s DNA was found in the room where Ms Kercher’s body was found (in contrast to that of Rudy Guede, a drug peddler from the Ivory Coast separately convicted of the murder). The other forensic evidence was hotly contested between experts. And the prosecution was allowed to propose a string of possible motives (including none at all).

So is Italian justice cockeyed? No, say its defenders: if anything, it is too scrupulous. Cases like this are not unprecedented. That of Adriano Sofri, a former radical left-wing leader accused of murdering a police officer, went through seven trials and appeals over 11 years from arrest to final (and still-controversial) conviction. Attempts to identify the serial killer known as the monster of Florence followed a similarly tortuous path, with the principal suspect dying before his final appeal was heard and his two alleged accomplices being convicted at least 26 years after the first murder.

An academic study in 2012* argued that American criticism arose from a misunderstanding of how Italian justice works. In Italy’s inquisitorial system, detailed appellate reviews “must be viewed as part of the plurality of voices the Italian justice system deems necessary to provide fairness and determine the truth.”

Yet, as the paper also acknowledges, the Italian system is not wholly inquisitorial. A reform in 1989 aimed to make it adversarial, as in English-speaking countries. But, as so often in Italy, it ended in compromise. There are no juries, for example, but lay judges sit with professional ones in more serious cases, so they rule on points of law as well as fact. Although media coverage is not restricted to what is said in court, and lay judges are susceptible to it, they are not sequestered (trials can last a year or more because hearings are not consecutive).

Antonio Manca Graziadei, president of the Italian branch of Avocats Sans Frontières, a lobby group, points to another problem. The 1989 reform transferred the supervision of investigations from the police to prosecutors. That, he says, both demoralised investigators and removed a vital check. Before, the police had to present their evidence to a prosecutor who, if he judged it inconclusive, would not proceed with a case. Now it is his own handiwork, and if he does not ask for an indictment, he may be accused of wasting public money. “There is an absence of independent scrutiny in the early stages,” says Mr Manca Graziadei. “If there is not really any solid proof, as a result of bad investigation, judges can take different views.”

* “Scales of Justice: Assessing Italian Criminal Procedure Through the Amanda Knox Trial” by Julia Grace Mirabella. Boston University International Law Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1, January 2012.