Federal justice officials, city of Portland can’t agree on judge’s request for …

May 30, 2014

Google Offers Webform To Comply With Europe’s ‘Right To Be Forgotten’ Ruling

May 30, 2014

Zygmunt Bauman

Throughout most of our electronic exchanges we tackle the issue of the “self” as such, and its “production” as such, concentrating on the features all selves and all cases of their production share, and only occasionally mentioning their diversities. But “selves” come in many shapes and colours, and so do the settings, mechanisms, procedures of their production – and indeed the very likelihood of their production being undertaken, pursued and seen through by the “auctors” (authors and actors rolled into one) presumed and expected to perform that task. Let me now try to survey, however briefly, the misleadingly even if inadvertently neglected other side of the phenomenon which we attempted to dissect and reconstruct in all its aspects.

I believe that an excellent point from which to start has been offered by Joseph Stiglitz and Göran Therborn in their outstanding, trail-blazing and stage-setting contributions to the recently resurrected and currently on-going public debate on social inequality, its devastating impacts and the frailty of prospects of its cure or even mitigation.[1] The picture painted by Stiglitz is best conveyed by a concise, but hologram-like statement: “We have empty homes and homeless people” (p.xli) As the complex canvass is inch by inch unravelled, what we come to see are “huge unmet needs” confronting “vast under-utilized resources” – idle workers and idle machines, cast out of service by chronically and systemically malfunctioning markets. Alongside unstoppably rising inequality, also the fairness and the sense of fair play(p.xlvii) fall collateral victims to that inanity.

Victims of inequality are not only those on the receiving side of economic, health, educational and social discrimination: as numerous social studies document, it affects the quality of life of the society as a whole. They show that the volume and intensity of most social pathologies correlates with the degree of inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) rather than with the average standard of living as measured by income per head. As Therborn puts it (p.21): “Inequality always means excluding some people from something. To be poor means that you do not have sufficient resources to participate (fully) in the everyday life of the bulk of your fellow citizens”. For the poor yet more than for those close above them, “the social space for human development is carved up and restricted” (p.22).

Therborn accepts, as the most correct of all on offer, Amartya Sen’s 1992 definition[2] of the norm which the state of inequality violates: “Equality of capability to function fully as a human being” – which means the capability of exercising what a given society in a given time considered to be inalienable human rights. And he goes along with Martha Nussbaum[3] pointing out that the rights which inequality violates, or for all practical intents and purposes denies, entail – alongside survival and health – also “freedom and knowledge (education) to choose one’s life path, and resources to pursue it” (p.41). Obviously, we can add therefore to that list of violated or denied rights the right to self-production and the resource indispensable to pursuing it.

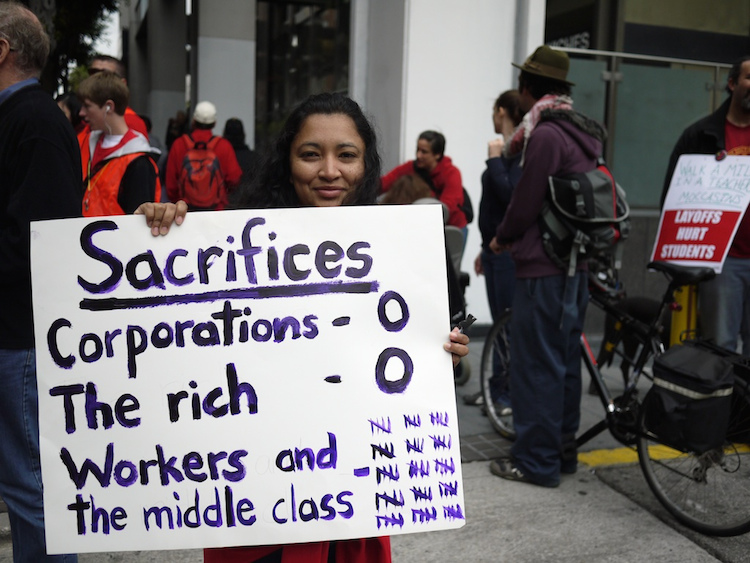

The ranks of those whose human rights so understood have in practice been seriously eroded or even downright expropriated are steadily rising; the number of those who manage to escape unscathed the effects of market tremors and turbulences are steadily shrinking. To a case study of those intertwined tendencies in operation Stiglitz dedicates a chapter entitled “America’s 1 per cent problem” (a phrase picked up soon later by the “Wall-Street Occupiers”). He found out that the number of citizens who “managed to hang on to a huge piece of the national income” despite the credit crash was confined to but one percent of the US population (p.2). Such a concentration of income at the very top of economic hierarchy was not, however, a novelty brought about by the recent economic catastrophe. “By 2007, the year before the crisis, the top 0.1 percent of America’s households had an income that was 220 times larger than the average of the bottom 90 percent. Wealth was even more unequally distributed than income, with the wealthiest 1 percent owning more than a third of the nation’s wealth”. Between 2002 and 2007 “the top 1 percent seized more than 65 percent of the gain in total national income”, whereas “most Americans were actually growing worse-off” (p.2-3). The average pay of CEOs has become more than 200 times greater than “that of a typical worker” (p.26). And all of these are, let’s note, statistical averages, failing to expose fully the person-to-person distances and their growth.

One of the most salient and probably the most seminal impacts of the impetuous growth and the profound transformation in the scale and dimensions of inequality is the sharp differentiation of the degrees of human autonomy and opportunities for self-definition, self-assertion, indeed the chances and capabilities of self-production allotted and available to individuals placed at different level of the wealth and income hierarchy.

Meritocracy was meant to lead to a flourishing middle class. It didn’t happen according to Zygmunt Baumann (photo: CC Paul Bailey on Flickr)

Inequality And The Middle Class

Let’s be clear about it: the idea of self-production was the invention, battle-cry and practice of the middle classes spreading between the upper classes who needed nothing to do in order to maintain their position a priori guaranteed by birth, and the lower classes which could do pretty little to change their – also imposed by birth – position. “Middle classes” belonged to the only (but growing and hoped to grow yet more) sector of society, to which the postulate of “meritocracy” (social rewards faithfully reflecting the value of individual offers) was addressed and tested in practice. It was widely expected that thanks to the entrenchment of the democratic mode of human coexistence the “middle class” will go on expanding at the expense of both, the top and the bottom, extremes of social pyramid – and, so the postulate of meritocracy, will spawn equality of opportunities for the whole of society – putting paid to class divisions and providing an effective remedy for the conflicts of class interests (remember the vision of the on-going “embourgeoisement” of the working class, a hard-core element in the 1960s social-scientific commonsense?)

Now, however, the middle classes are conspicuous primarily by the shrinking of their ranks, of their trust in the increasingly vague and ethereal promises of meritocratic creed, and of their hopes. They watch, haplessly and helplessly, the capabilities of self-creation and self-assertion being levelled down, not up, degrading them to the fixity of fate previously reserved for the lowest strata of social hierarchy. Guy Standing[4] coined the term “precariat” to denote the new predicament and the emerging mode of life and thought of the categories of people not so long ago classified as members of the “middle classes”. That term refers to the endemic precariousness (instability, fitfulness, capriciousness, shakiness, and all in all vulnerability) of existence: a condition which several dozens of years ago were deemed to be a particular, class-defined bane of the “proletariat”.

Now the middle classes, in droves, are pushed and pulled to savour the bitter taste of the condition of which Lyndon Johnson, when launching his project of the “Great Society” famously opined that a man cast into it is not – and can’t be – free. Whereas “not free” means, first and foremost: stripped of capability to self-create, to choose, to shape up, and to control one’s mode of life. We are all, or mostly, middle class now: but not the sort of middle class which Abbé Sieyès had in mind when almost two and a half centuries ago he boisterously and proudly declared the “third estate” to “be everything”.

“The prospects of a good education for the children of poor and middle-income families” (Stiglitz, p.118) are “far bleaker than those of the children of the rich”. “Parental income is becoming increasingly important, as college tuition increases far faster than incomes…” (ibid.) “As those in the middle and at the bottom struggle to make a living… families have to make compromises, and among them is less investment in their children” (p.119). In other words, just as in the case of the Hebrew slaves in Egypt, who were told to go on producing as many bricks as before though without the straw until now supplied by the pharaoh’s agents, the offspring of the middle- and low-income families are told to go on self-producing as they did before though this time without the tools which such production requires.

And so: goodbye to the dreams of meritocracy; lasciate ogni speranza you, who enter a world in which, in Stiglitz’s summary, “we are not using one of our most valuable assets – our people – in the most productive way possible” (p.117). In other words, when the bulk of those entering are booked to the debit, not to the credit of that world. And when up to half of new entrants are forced to accept jobs (in case they are lucky to find any) much below their ambitions, talents and skills, and offering little or no security, let alone a chance of self-assertion. And when they watch a steadily growing number of their elders who seem to have thus far managed to compose respectable and gratifying selves but now in their fifties find their hard won and laboriously composed identities denied, their hard won and cherished position in society withdrawn, and themselves relegated to the category of redundant and social liabilities. And let us recall that the selection of an “lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate” inscription to be engraved on its entry gate Dante chose for the trademark of hell.

What We Can Learn From The European Parliament Elections?

We can much learn about the probable outcomes of that profound change from the results of the recent elections to the European Parliament. Those elections, unlike the elections to national parliaments, are believed to have little if any practical impact on the conditions under which the electors expect to conduct their life struggles in the foreseeable, let alone a more distant future. They serve the electors instead as a sort of safety valve: occassions to let off the explosion-prone excess of steam, to vent off the blood-poisoning grievances and get rid for a time of potentially toxic emotions – and all that into a relatively safe, because inocuous and inconsequential, direction. The most salient mark of the last European parliamentary elections was an unprecedented proportion of electors deploying that occasion in full and coming to the polling booths for no other purpose except shouting “Woe!”, “Good Heavens!” – and “Help!”: such pleas having been notably deprived of a specific address defined in currently established political terms. As Timothy Garton Ash summed it up in a recent issue of The Guardian”:[5]

So what were Europeans telling their leaders? The general message was perfectly summed up by the cartoonist Chappatte, who drew a group of protesters holding up a placard shouting “Unhappy” – and one of their number shouting through a megaphone into the ballot box. There are 28 member states and 28 varieties of Unhappy. Some of the successful protest parties really are on the far-right: in Hungary, for example, Jobbik got three seats and more than 14% of the vote. Most, like Britain’s victorious Ukip, draw voters from right and left, feeding on sentiments such as “we want our country back” and “too many foreigners, too few jobs”. But in Greece, the big protest vote went to the leftwing, anti-austerity Syriza.

This is why I believe the lessons of these elections to be especially illuminating for the theme of our conversation. Unhappiness was indeed, it seems, what prompted citizens of Europe to vote (note that for the first time in EU history the number of voters did not fall), even if the assumed/putative culprits of their unhappiness differed from one country to another. For all one can guess, few of the people coming to express their unhapiness and vent in public their wrath trusted any of the people on the list of candidates to be able to alleviate their misery and any of the competing programmes on sanitation to be effective. What moved a great number of the electors was rather a “frustration fatigue”, the dashing of hopes that (as Peter Drucker warned already a few decades ago) the salvation promised, but not coming “from on high”. The protest against the direction in which things are currently going, the most vociferous message of these elections, was not directed against any particular section of the extant political spectrum – but at politics in its present shape, usurped as it is – or is widely believed to be – the elites increasingly aloof and distant from the problems which occupy most of the time and absorb most of the energy of “ordinary people”. That politics as a whole is seen by many as nearing bankruptcy – no longer able to assure the regular supply of straw needed to make the bricks.

Neal Lawson, the head of “Compass” (an organization introducing itself on its web page as “building a Good Society; one that is much more equal, sustainable and democratic than the society we are living in now”)[6], and one of the most insightful and inventive minds on the British political stage, interprets the results of the European elections as a loud call to vindicate the citizens right to a “citizen-led politics of everyday democracy, not just a vote once every five years”. “The election result”, he suggests

makes the case for a new politics overwhelming. The future can neither be denied nor avoided. The world is changing – we either bend it to us, to build a good society, or we will be forced to bend to it. Which way it goes depends on our ability to change and on how good we are at politics – our wit, wisdom, insight, good faith and perseverance. Now more than ever, we cannot say we weren’t warned.

To what he adds words of encouragement: “at the very time the old politics is disintegrating, new ways of being and doing are opening up that give us hope.”

The European elections are seen as an opportunity to let off steam without big consequences says Zygmunt Baumann (photo: CC European Parliament on Flickr)

The Expropriation Of Politics

If there was a common denominator to the unhappiness manifested by the otherwise starkly disparate categories of Europeans, it was – or so at least it seems to me – by the practical, if not explicit, expropriation of politics from the citizens whom it was meant and designed to serve. But, as Abraham Lincoln proposed and insisted a long time ago, no man is good enough to govern another man without the other’s consent. Self-production, self-composition and self-assertion are not only some among many inalienable human rights, but also the building blocks of the “citizen-led everyday democracy” which Lawson had in mind.

Mauro Magatti and Chiara Giaccardi, professors of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan, several weeks ago published a fundamental study under a challenging title Generativi di tutto del mondo unitevi![7]. The subtitle defines their oeuvre as a “Manifesto of a society of freedom”. In the centre of the authors’ attention are (to express it in my own idiom) the chances and the prospects of the “re-subjectification of work”, or of restoration to workers the status of subjects (or of “auctors” – personal unions of authors and actors) of which they were expropriated in the course of modern history. It is in order to denominate the product of the reunification of actor’s and author’s roles, that Magatto and Giaccardi coined a new concept of “generativo“. The semantic gist of that concept is perhaps best conveyed in English as “creative individual”.

Magatti and Giaccardi neither suggest pushing back the clock of history nor demand retreat from the modern individualization that alongside introducing new threats to the self opens after all new horizons for individual contributions to the material and spiritual wealth of the human Lebenswelt. To act generatively, they write, means to decide the value and to make it flesh. That value is precisely the enrichment of the world we share, not its impoverishment, as in the hunter’s style, privatized utopia. The logic of “generativity” is at cross-purposes with the logic of consumerism. It is not guided by the will of “incorporation” (that is, appropriation of things and withdrawing them by the same token from circulation and shared use and enjoyment), but by the intention and practice of “excorporation”: “Generativity is a mode of life the purpose of which is assisting others in their being, care of their life and volume of their life resources”.

Freedom of individual self-assertion combined with generative personality are capable of multiplying the material and spiritual affluence of the human world, and with it – and thanks to it – also the meaningfulness and moral quality of human existence and coexistence. Such combination, if we succeed in the effort to substitute it for the present-day mode of self-creation and self-assertion based as they are on rivalry instead of collaboration, has a chance of preventing the demotion of humanity to the level of a zero-sum game. Freedom of individual self-definition united with the practice of “excorporation” is a warrant of growing richness and diversity of human potential – but also of enhancing the space for all of us and each of us self-definition and self-constitution. Solidarity of fate and endeavours derived from and supported by generativity won’t stand in opposition to the purpose of individual self-assertion; quite on the contrary, it would become its best – the most loyal and reliable – ally. Such solidarity is, in fact, a necessary condition and best warrant of its success.

[1] See Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality, Penguin Books 2013, and Göran Therborn, The Killing Fields of Inequality, Polity Press 2013.

[2] In Inequality Reexamined, Harvard Up, chap.3.

[3] See her Creating Capabilities, The Belknap Press 2011

[4] See his Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, Bloomsbury 2014.

[5] http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/may/26/europe-unhappy-european-union

[6] See http://www.compassonline.org.uk/about/

[7] Feltrinelli 2014.

This essay is from the forthcoming book “Self-production of Self”, in conversation with Professor Rein Raud of Tallinn University, to be published by Polity Press.

Have something to add to this story? Share it in the comments below.